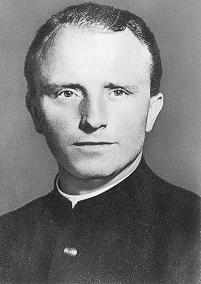

The subject of our blog post today was given two monikers by the French: L’Aumonier de l’enfer or, the “Minister in hell” and L’Archange des prisons or, the “Archangel of the prisons.” Many people in the Catholic Church would like to give him a third one: “Saint” but I decided to choose “Archangel” to be the title of this blog. However, of the two French names, considering the tactics and ruthlessness of the Nazis and Gestapo in particular, the first title might have been more appropriate.

Did You Know?

Did you know that even government postal services make mistakes? If you didn’t, then you’ve never had your mail delivered to the wrong address or vice versa. Well, the Royal Mail of Britain just made a major blunder.

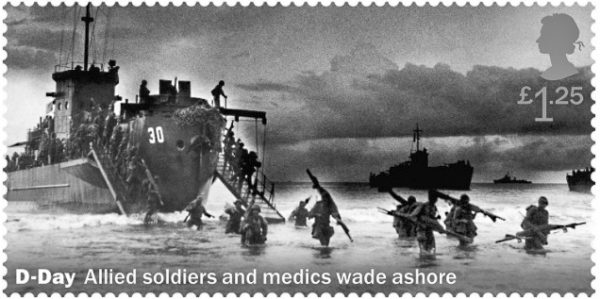

To commemorate the 75th anniversary of the D-Day landings (6 June 1944), the Royal Mail designed a stamp using a photo of American troops knee-deep in water as they left their landing craft to storm the beach. The stamp’s caption reads, “D-Day: Allied soldiers and medics wade ashore” ⏤only one problem.

The image used was a landing sometime in May 1944 in Dutch New Guinea (part of Indonesia). It was not Normandy. Almost immediately, social media was atwitter with comments about the errors (it’s easy to determine the landing craft were different than those used on the Normandy beaches and the men getting off are medics carrying stretchers).

I collect stamps (a dying hobby like model trains and bridge playing I suppose). Since stamps were invented, there have been some real whoppers of mistakes. Take for example, the American “Inverted Jenny” stamp with an upside-down aircraft (no, it wasn’t meant to honor air shows). Today, a mint and never-hinged inverted jenny stamp is worth around $1.6 million. Britain is also known for mistakenly issuing stamps without the head of the monarch (if it was King Charles I, it wouldn’t have been a mistake) or without perforations along the edges. This time however, the Royal Mail caught the problem before any stamps were printed and got out into the public.

Too bad for us collectors (and the auction houses). So, the next time it happens, would all of you on social media please be quiet and don’t say anything ⏤ it ruins the fun (and our bank account).

Let’s Meet Abbe Franz Stock

Franz Stock (1904-1948) was born in a small village in Germany along with eight other brothers and sisters. Attending a Catholic-run elementary school, Franz made the decision to become a priest by the time he was twelve. In his early twenties, Franz entered the Catholic seminary in Paderborn, Germany. Several years later, Franz moved to Paris where he spent several years studying at the Institut Catholique (reportedly, he became the first German student of theology in France since the Middle Ages). Ordained in March 1932, Father Franz was assigned to the town of Effeln, northeast of Dusseldorf, Germany. Two years later, Franz returned to Paris where he lived at 23, rue Lhomond (5e) while serving as rector to the German parish.

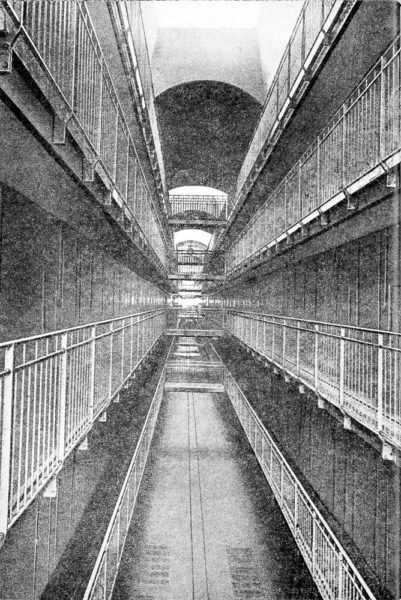

Several days after the Nazis invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, Franz returned to Germany. However, he was assigned once again to Paris in October. His job was to administer to the prisoners in Nazi controlled prisons such as Fresnes, La Santé, and Cherche-Midi.

Prison Priest

Franz was officially named as the priest to the military post on 6 October 1941. His responsibilities included caring for the prisoners and getting those condemned to die ready for execution. Between 1941 and 1944, the Paris prisons held approximately 11,000 inmates, both criminal as well as political including hostages and résistants. Often, prisoners either committed suicide or were executed in the prison without a trial or advance notice. Most of the condemned prisoners were transported out of the city to the western suburbs of Paris called Suresnes.

Fort Mont-Valérian

One of the forts built in the mid-1800s to protect Paris, Fort Mont-Valérien was used by the Nazis during the occupation as a prison. At that time, Suresnes was a rather remote location and the Germans knew that executions at Fort Mont-Valérien would not attract any attention.

Condemned prisoners would be brought in from the various Paris prisons by trucks and dropped off in front of a small chapel in the wooded area. There they would wait until it was their turn to walk the 100 meters (328 feet) down the path to a clearing in the woods. Typically, groups of four to five would be taken at one time. In the clearing stood five poles. They were tied to the poles, blindfolded, and then shot by a German firing squad. The memorial bell reflects the names of the 4,500 men who were executed in the clearing (French law prohibited women from being executed on French soil so, the Nazis sent them to Germany to be beheaded).

Father Stock’s Diary

Franz kept a diary during this time, and he mentions 863 specific executions. Later, he indicated that he attended many more and estimated that it was likely around 2,000 executions he witnessed. It was as chaplain to Fort Mont-Valérien that he earned the nicknames previously mentioned. Franz was allowed unrestricted access to the prisoners and at great personal risk, he took advantage of his position to assist the condemned.

L’Archange des Prisons

Franz passed prisoner’s messages onto their families as well as bringing clandestine messages back to them. The inmates could count on Franz bringing them books, food, and clothes. He also divulged German information to somehow help the families if they were interrogated. Technically, Franz was a non-commissioned officer in the Wehrmacht. If he had been caught, it is likely Franz would have been executed for treason (two of his aides were caught and transferred to the front lines).

One of the last prisoners whom Franz cared for was Suzanne Spaak (1905-1944). She had been arrested in 1942 for her resistance activities which included saving more than 1,000 Jewish children. Kept in Fresnes Prison in horrible conditions, Suzanne wrote to her children and husband and the letters were carried out and delivered by Franz. Her last letters were dated 12 August 1944. That day, twelve days before the liberation of Paris, Suzanne and one other résistant were taken to the prison courtyard and shot (despite Berlin’s clemency order for Suzanne which was either ignored or misplaced during the chaos of the Germans exiting Paris). Two months later, the letters were found in an envelope delivered to her brother-in-law, Paul-Henri Spaak, the Belgium Foreign Minister. Inside the envelope was also the burial record for a grave in the Bagneux Cemetery just north of Fresnes Prison. Abbé Franz Stock had delivered one last piece of prisoner correspondence and information for the family.

Prisoner of War

On 25 August 1944, the day of liberation, Father Stock was in the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital tending to 600 German soldiers and 200 Allied soldiers. The Americans took Franz prisoner and sent him to Cherbourg. While in the POW camp, Franz was contacted by the Aumônerie Général in Paris (the Military Chaplain of Paris) who asked him to become the managing director of a new seminary. They wanted a core of captured Catholic theology students to become the foundation of Catholic renewal in Germany. The seminary was located in the POW Camp Dépôt 51 in Orléans and twenty-eight students were waiting for him.

Post-War

By mid-August 1945, the seminary and its 160 seminary students moved to POW Camp Dépôt 501 near Chartres, sixty miles south of Paris. Abbé Stock and the seminary, séminaire des barbelés, were frequently visited by the bishop of Chartres as well as Nuncio Roncalli, the future Pope John XXIII (1881-1963). On 5 June 1947, the seminary was closed. A total of 949 lecturers, priests, brothers, and students had passed through the seminary during its successful two-year existence. Franz was appointed an honorary doctor of the University of Freiburg in mid-December 1947. Two months later, Abbé Franz Stock unexpectedly died in Paris. All along, Franz suffered from serious heart disease which he never disclosed to anyone.

At the time of his death, Franz was still considered to be an Allied POW. As such, very few people were made aware of his death. Nuncio Roncalli officiated at the funeral and accompanied by only twelve people, Franz’s remains were buried at Thiais Cemetery in Paris. The families of the prisoners he assisted paid for the headstone. In 1963, his coffin was removed and re-buried at the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Church in Chartres on Pope John XXIII’s orders which the dying pope signed on his death bed.

Abbé Franz Stock is also memorialized at Fort Mont-Valérien. The immense plaza in front of the Mémorial de la France combattante is named for Franz ⏤Place del’Abbé Franz Stock. It is a fitting gesture to a man who served the needs of the other men memorialized on the bell opposite the small chapel.

Recommended Reading and Viewing

Cameron, Claire (Editorial Director). Le Mont-Valérien: Résistance, Répression Mémoire. Montreuil: Éditions Gourcuff Gradenigo, 2010.

Nelson, Anne. Suzanne’s Children: A Daring Rescue in Nazi Paris. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017.

Friends of Franz Stock Association: Link here.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

I’m grateful to the Friends of Franz Stock Association and in particular, Jean-Pierre Guérend for allowing me to use the images of the execution of the résistants. M. Guérend and the association are dedicated to preserving the memory of Franz Stock and promoting his advancement to sainthood. Please visit the association’s website above to view the memorial at the former seminary in Chartres. This is a mutual internet portal for the German and French committees.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you. The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs. Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright ©2019 Stew Ross